When Kabul fell to the Taliban in 2021, the 15 students who had just arrived at the University of Missouri-Columbia found themselves stranded. It was a situation repeated on many campuses across the globe for Afghan students studying abroad.

Now, they have a student in their midst telling their stories . Voice of America freelance journalist Zabihullah Ghazi, currently a fellow at the University’s School of Journalism, covered his fellow students in their efforts to enhance greater understanding of Afghanistan and its culture with local residents.

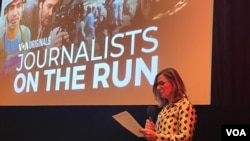

Ghazi shares his own harrowing story of flight from the Taliban, related through video and a first-person account in the VOA documentary, “Journalists on the Run.” Hosted by the journalism school, the film was screened at a nearby art-house cinema on October 12. The movie follows the journeys of three VOA journalists who each found their way to the U.S. in the aftermath of the Taliban takeover.

“Ghazi, Maryam [Khamosh] and [Zafar] Bamyani are representative of the hundreds of journalists in Afghanistan who faced down threats for doing journalism,” Acting VOA Director Yolanda López told the audience that nearly filled the auditorium at Columbia’s Rag Tag Cinema.

“You can’t sleep at night with these things happening,” said López, who had worked around the clock with VOA teams in Washington and South Asia in August 2021 to bring many VOA journalists to safety after the Afghan government’s fall.

At the screening, López was part of a panel discussion that included Ghazi, VOA Afghan Service Chief Hasib Alikozai and VOA documentary commissioning editor Lauren Kawana, who joined virtually. The University of Missouri’s Press Freedom Chair, Kathy Kiely, and Stacey Woelfel, director of the school’s documentary program, moderated the discussion.

Ghazi expressed the hope that someday he could bring his journalism skills home to Afghanistan. “Because my country is my love,” he said.

“I see hope in the little girls who want to go back to school,” Alikozai said in the far ranging discussion of the Taliban’s targeting of girls education and press freedom. He noted the youth’s continuing presence on social media in the country, “That gives me hope that they will continue to hold those in power accountable through citizen journalism.”

Alikozai said since the Taliban took power, the number of press outlets in Afghanistan has fallen from 540 to 320, with women journalists being the most affected. And still, Alikozai said VOA is reaching more than 80% of the audience in the country through FM and medium wave (AM) radio, satellite TV and on digital platforms.

Some journalists, like Ghazi, who left Afghanistan now work for VOA as freelancers, covering the ever-widening Afghan diaspora.

It’s a world war for free speech, Prof. Kiely said, with many news organizations enabling refugee journalists to work, as more regions of the world experience crackdowns on journalism.

“And so, at VOA, we’ll continue to tell the stories in countries where there is no freedom of the press – yes, Afghanistan, and China, Russia, Iran, Somalia, and too many others,” López told the crowd at the screening. “In telling these stories, we provide voice to the voiceless. And we hope our journalism will encourage everybody to pitch in to protect journalism and democracy.”

One of Ghazi’s next stories in the central Missouri city is to relate the struggle of Afghan families who have landed in the area, even as the local non-profit organization, City of Refuge, works to bring more uprooted Afghans to town.